尽管在过去的一个世纪里,内科学、外科学和血管内治疗取得了长足的进步,产妇死亡率已经显著地下降[9]。无论发达国家还是发展中国家,产后出血都是引起孕产妇死亡的重要原因[6]。据估计全球严重产后出血发病率约占分娩活婴产妇的11%[15]。

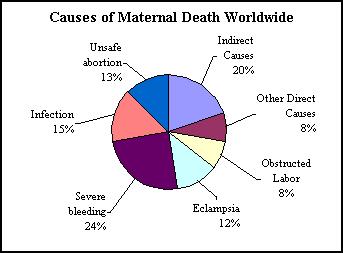

特别是在发展中国家发病率要高得多,那儿许多妇女分娩时没有技术熟练的助产士,也不常规积极处理第三产程,产后大出血占产妇死亡的1/3(25~30%)[18],在发达国家也是最常见的产妇并发症[10,13,14]。英国孕产妇死亡安全调查提供的因PPH的孕产妇死亡率为1.0/10万。在2000-2002年的3年间,261例孕产妇死亡中仅有10例死于PPH[16]。南非孕产妇死亡安全调查表明,PPH是孕产妇死亡的第三位最常见原因,在2002-2004年3年间总3406例孕产妇死亡中占313例[17]。报道医疗机构死亡的南非报告显示,大部分PPH死亡者(40%)发生在初级医疗机构,如诊所或地区医院。 报告认为产妇/社会相关因素、缺少急救交通工具、缺少输血血液、缺少技术合格的人员和不标准治疗全都是可以避免的因素。

产后出血的发病率取决于所应用的对产后出血定义。 常用的定义是出血超过500ml,其并发症发生率为所有生产的18%[10,11]。更为严重的出血为超过1000ml,发生率约为1~5%[12]。每年发生约14,000,000产后出血,病死率为1%[7]。产科并发症作为妊娠的结局的一种比妊娠死亡率更多被关注[8]。

产后出血(PPH)发生率为2~11%[1~3]。威胁生命PPH为1/1000产妇[4],每年由于PPH死亡的产妇为125 000[5]。子宫弛缓是PPH的主要原因,占所有出血的70%-80%

1. L Gilbert, W Porter and V A Brown, Postpartum haemorrhage – a continuing problem. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 94 (1987), pp. 67–71.

2. H A Brant, Precise estimation of postpartum haemorrhage: difficulties and importance. British Medical Journal i (1967), pp. 398–400.

3. M Newton, LM Mosey and G E Egli, Blood loss during and immediately after delivery. Obstetrics and Gynaecology 17 (1961), pp. 9–18.

4. G Lewis and J O Drife, Why mothers die. A report on the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom, 1994–96 (1998).

5. J Drife, Management of primary postpartum haemorrhage. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 104 (1997), pp. 275–277.

6. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006;367:1066–1074.

7. WHO. Maternal mortality in 2000. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA. Geneva: Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization, 2004.

8. Waterstone M, Bewley S, Wolfe C. Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: case-control study. BMJ 2001;322:1089–1093; discussion 1093-1084.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Healthier mothers and babies, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 48 (1999), pp. 849–858.

10. P.C. Devine, Obstetric hemorrhage, Semin Perinatol 33 (2009), pp. 76–81.

11. D.R. Elbourne, W.J. Prendiville, G. Carroli, J. Wood and S. McDonald, Prophylactic use of oxytocin in the third stage of labour, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2001) CD001808.

12. E.F. Magann, S. Evans, S.P. Chauhan, G. Lanneau, A.D. Fisk and J.C. Morrison, The length of the third stage of labor and the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, Obstet Gynecol 105 (2005), pp. 290–293.

13. T.F. Baskett and C.M. O'Connell, Severe obstetric maternal morbidity: a 15-year population-based study, J Obstet Gynaecol 25 (2005), pp. 7–9.

14. W.H. Zhang, S. Alexander, M.H. Bouvier-Colle and A. Macfarlane, Incidence of severe pre-eclampsia, postpartum haemorrhage and sepsis as a surrogate marker for severe maternal morbidity in a European population-based study: the MOMS-B survey, Br J Obstet Gynaecol 112 (2005), pp. 89–96.

15. Abou-Zahr C . The global burden of maternal death and disability. British medical bulletin 2003;67:1-11.

16. Why mothers die . 2000-2002. The report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. CEMACH, London, RCOG Press 2004;86-93.

17. Saving mothers . 2002-2004. The report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa. Third report on confidential enquiries into maternal death in South Africa. Department of Health, South Africa 2006:68-95.

18. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006;367:1066–1074.

|