肝癌在世界范围内占癌症死亡原因的第三位,由于环境作用或慢性肝炎所引起,但它们之间的联系并不很清楚。 慢性乙型肝炎在缺乏医疗资源的国家是HCC最常见的原因 [1]。实际上,在世界上的所有HCCs超过一半归因于慢性乙型肝炎[2]。在从20世纪80年代的一个根据人口的队列研究中,涉及22,708个中国台湾人随访8.9年,HCC的发生比HBV携带者比非HBV携带者高出98.4倍[3]。在台湾2010随后进行研究显示,甚至非活性HBV携带者(无症状,肝功能正常,HBV少量的复制和血液中不能发现病毒或水平较低)与正常人比较发生肝癌的风险增加四倍[4]。

乙肝携带者肝癌风险和发生似乎取决于种族。在进行性肝硬化期后,白种人乙型携带者倾向年龄较高的时候发展成肝癌。而亚洲和非洲的患病个体,往往在青少年期或中年发育成肝癌,而且和白种人的乙肝携带者比较,亚洲或非洲病人较少呈现肝硬化的迹象。背后的遗传差异可能与这些种族的差异有关。另外,这种差异还可能被解释为获得乙肝病毒感染在不同种族的年龄差异:垂直传播是乙肝病毒在亚洲人感染的主要途径,而婴幼儿期的水平传播是非洲人传播的主要途径。对比之下,西方国家乙肝病毒主要是在青少年和青年中通过高风险行为传播,如静脉吸毒,性接触或医源性原因包括输血,不安全的针穿刺操作,侵入性操作,血液透析或器官移植等原因。 在过去的几年中,计算预测乙肝携带者患肝癌的风险一直在发展[5,6]。特定乙肝病毒基因型或乙肝病毒株进行共同突变(包括基本核心启动子突变和前S缺失突变)增加肝癌风险,就像乙肝高负荷,高龄,男性,持续乙肝病毒复制和感染持续时间长一样[7-12]。

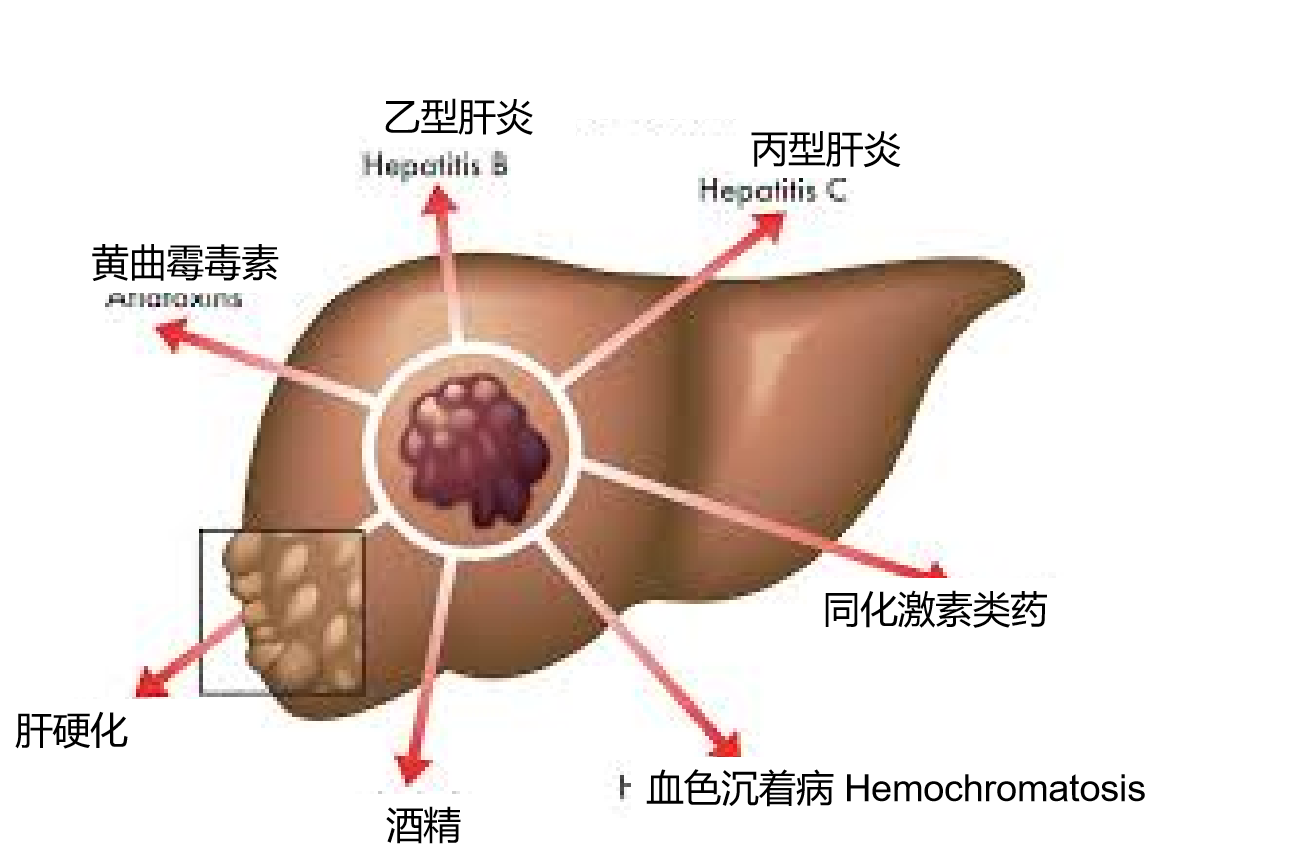

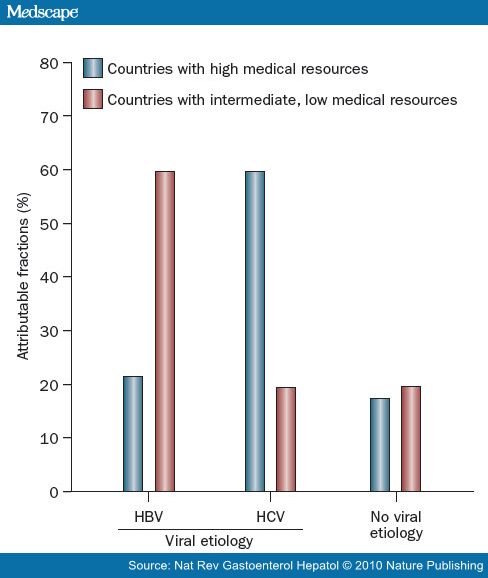

在21号染色体上第二类细胞因子受体基因组包括IFNAR2(编码的I型干扰素受体)和IL10RB(编码为IL - 10的相关细胞因子受体,其中包括干扰素λ家族)[13]。这一组与乙型肝炎的持久性关系密切。在这个位点的保护性等位基因比起西非黑人更多出现在欧洲白人。乙肝病毒基因型的不同也可能在一定程度上解释了不同种族之间的肝癌风险差异。乙型肝炎病毒基因型C最常见于亚洲人,并发现与在乙型肝炎e抗原(HBeAg)血清持续存在关联,e抗原的自发清除率下降,HBeAg清除后,HBeAg血清阳复原率增加,肝癌风险增加,与乙肝病毒DNA的病毒载量水平无关[8,14-16]。 丙型肝炎病毒 包括美国在内,多数西方国家丙型肝炎是慢性肝脏疾病和肝癌的主要原因 (上图) [17]。在一项大样本,基于人口调查的研究中,12,008个台湾男性随访9.2年,HCV抗体血清反应阳性的个体比较血清反应阴性的个体HCC的的风险增加20倍[18]。与HBV对比,HCV垂直传播是非常罕见的,虽然病毒RNA母亲水平高与婴儿HCV感染率增加[19,20]。HCV通常通过血液的直接暴露传染,例如静脉内药物或高危险的性行为[21]。HCV医原性传输通过污染的针、注射器和其他医疗仪器和操作也是常见的[22-24]。在一项2002年出版西班牙的研究中在入院(67%)是最常见的危险因素,超出急性HCV感染(45%是为外科手术,33%是内科病房入院,22%入院进行侵入性操作),其后是静脉内药物应用(8%),偶然针刺伤(5%)和性接触(6%)[25]。自从1992年捐赠的血液的HCV筛查程序的实施,在多数发达国家HCV从输血传染的风险的少于0.03%/每单位[26,27]。其他潜在的传输途径包括鼻内可卡因应用, 划伤,血液抽吸,文身和身体穿洞[24]。伴随酗酒,糖尿病,潜在HBV传染,年龄增加,同属黑人族群,低血小板计数、高水平碱性磷酸酶,血管曲张和抽烟等似乎都增加HCV患者患HCC的风险[28-32]。 合并症及环境因素 在丙型肝炎后,酒精性肝病是美国第二大常见的肝癌危险因素[33]。由于酒精代谢的性别差异,对于酒精引起的肝损伤女性比男性更敏感,在等效酒精摄入的情况下,女性比男性更容易发展到肝硬化[34]。同时存在病毒肝炎的情况下,过度饮酒增加肝癌的风险[28,35]。非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(NASH)也正在成为许多发达国家肝癌一个危险因素[42,36]。肥胖,为NASH的主要危险因素,一直在美国不断地增加。当代的调查数据显示,美国成年人中有三分之一是肥胖[37,38]。NASH的人越来越多(作为肥胖和代谢综合征患病率增加的结果),相信有助于肝癌的发病率不断上升。很少以人口研究为基础的数据支持这个假设,因为伴随肝硬化形成时,脂肪肝已经消失,在肝癌被诊断时很难证明NASH的历史。 黄曲霉毒素B是一种霉菌毒素,在肝癌发病机制上与乙肝病毒相互协同[39]。黄曲霉毒素导致DNA突变,特别是TP53的基因,减弱p53抑癌作用。在医疗资源欠发达地区,如撒哈拉以南非洲和东亚,这种霉菌毒素经常污染食物。努力消除黄曲霉毒素B污染,特别是在高水平暴露的地区,包括中国和西非的行动正在进行中[40,41]。

HCC危险因素(世界胃肠病组织全球指南)

伴随着乙肝疫苗注射的普及和HCV感染的下降,西欧HCC的发病率将在5~10年(2016~2021)后下降。那时代谢综合征、糖尿病、非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(non-alcoholic steatohepatitis)和酗酒将成为肝癌的主要危险因素。 1. Bosch, F. X., Ribes, J., Diaz, M. & Cleries, R. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology 127 (Suppl. 1), S5-S16 (2004). 2. Parkin, D. M. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int. J. Cancer 118, 3030-3044 (2006). 3. Beasley, R. P Hepatitis B virus. The major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 61, 1942-1956 (1988). 4. Chen, J. D. et al. Carriers of inactive hepatitis B virus are still at risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and liver-related death. Gastroenterology 138, 1747-1754 (2010). 5. Yuen, M. F. et al. Independent risk factors and predictive score for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. J. Hepatol. 50, 80-88 (2009). 6. Yang, H. I. et al. Nomograms for risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 2437-2444 (2010). 7. Liu, S. et al. Associations between hepatitis B virus mutations and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 101, 1066-1082 (2009). 8. Yang, H. I. et al. Associations between hepatitis B virus genotype and mutants and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 100, 1134-1143 (2008). 9. Kao, J. H. Role of viral factors in the natural course and therapy of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol. Int. 1, 415-430 (2007). 10. Chen, C. J. et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 295, 65-73 (2006). 11. Yang, H. I. et al. Hepatitis B e antigen and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 168-174 (2002). 12. Yang, H. I. et al. Hepatitis B e antigen and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 168-174 (2002). 13. Frodsham, A. J. et al. Class II cytokine receptor gene cluster is a major locus for hepatitis B persistence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 9148-9153 (2006). 14. Chu, C. J., Hussain, M. & Lok, A. S. Hepatitis B virus genotype B is associated with earlier HBeAg seroconversion compared with hepatitis B virus genotype C. Gastroenterology 122, 1756-1762 (2002). 15. Chu, C. J. et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes in the United States: results of a nationwide study. Gastroenterology 125, 444-451 (2003). 16. Livingston, S. E. et al. Clearance of hepatitis B e antigen in patients with chronic hepatitis B and genotypes A, B, C, D, and F. Gastroenterology 133, 1452-1457 (2007). 17. Di Bisceglie, A. M. et al. Hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: influence of ethnic status. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 98, 2060-2063 (2003). 18. Sun, C. A. et al. Incidence and cofactors of hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study of 12,008 men in Taiwan. Am. J. Epidemiol. 157, 674-682 (2003). 19. Lam, J. P et al. Infrequent vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus. J. Infect. Dis. 167, 572-576 (1993). 20. Ohto, H. et al. Transmission of hepatitis C virus from mothers to infants. The Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus Collaborative Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 330, 744-750 (1994). 21. Alter, M. J. et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 556-562 (1999). 22. Bronowicki, J. P. et al. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis C virus during colonoscopy. N. Engl. J. Med. 337, 237-240 (1997). 23. Mele, A. et al. Risk of parenterally transmitted hepatitis following exposure to surgery or other invasive procedures: results from the hepatitis surveillance system in Italy. J. Hepatol. 35, 284-289 (2001). 24. Karmochkine, M., Carrat, F., Dos Santos, O., Cacoub, P. & Raguin, G. A case-control study of risk factors for hepatitis C infection in patients with unexplained routes of infection. J. Viral Hepat. 13, 775-782 (2006). 25. Martínez-Bauer, E. et al. Hospital admission is a relevant source of hepatitis C virus acquisition in Spain. J. Hepatol. 48, 20-27 (2008). 26. Donahue, J. G. et al. The declining risk of post-transfusion hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 327, 369-373 (1992). 27. Schreiber, G. B., Busch, M. P, Kleinman, S. H. & Korelitz, J. J. The risk of transfusion-transmitted viral infections. The Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 1685-1690 (1996). 28. Hassan, M. M. et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: synergism of alcohol with viral hepatitis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology 36, 1206-1213 (2002). 29. Ikeda, K. et al. Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen and risk for hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Ann. Intern. Med. 146, 649-656 (2007).

30. Ohki, T. et al. Obesity is an independent risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma development in chronic hepatitis C patients. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 459-464 (2008).

31. Lok, A. S. et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and associated risk factors in hepatitis C-related advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology 136, 138-148 (2009).

32. Chen, C. L. et al. Metabolic factors and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by chronic hepatitis B/C infection: a follow-up study in Taiwan. Gastroenterology 135, 111-121 (2008).

33. El-Serag, H. B. & Mason, A. C. Risk factors for the rising rates of primary liver cancer in the United States. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 3227-3230 (2000).

34. Frezza, M. et al. High blood alcohol levels in women. The role of decreased gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity and first-pass metabolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 322, 95-99 (1990). 35. Donato, F. et al. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma: the effect of lifetime intake and hepatitis virus infections in men and women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 155, 323-331 (2002). 36. Adams, L. A. et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 129, 113-121 (2005). 37. Flegal, K. M., Carroll, M. D., Ogden, C. L. & Curtin, L. R. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA 303, 235-241 (2010). 38. Ogden, C. L. et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA 295, 1549-1555 (2006). 39. Qian, G. S. et al. A follow-up study of urinary markers of aflatoxin exposure and liver cancer risk in Shanghai, People's Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 3, 3-10 (1994).

40. Yu, S. Z. Primary prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 674-682 (1995).

41.Turner, P. C. et al. The role of aflatoxins and hepatitis viruses in the etiopathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma: A basis for primary prevention in Guinea-Conakry, West Africa. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17 (Suppl.), S441-S448 (2002). 42. Marrero, J. A. et al. NAFLD may be a common underlying liver disease in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatology 36, 1349-1354 (2002). |